መነሻ ገጽ » ጥቂት ስለ አገሪቱ ሥርዓት » እስራኤል

Overview of Israel

- History of Israel

- Hierarchical structure

- The Constitution of Israel

- Federal Government

- Local Government

- Elections

History of Israel

The history of the Jewish people, and their roots in the Land of Israel, spans thirty-five centuries. It is here that the culture and religious identity of the Jewish people was formed. Their history and presence in this land have been continuous and unbroken throughout the centuries, even after the majority of Jews were forced into exile almost 2,000 years ago. With the establishment of the State of Israel on May 14, 1948, Jewish independence was renewed.

Early History: In the first century, when the Jewish civilization in Israel was already over 1,000 years old, Rome destroyed the Holy Temple in Jerusalem and conquered the Jewish nation. At this time, the Romans renamed the region “Palestine” and exiled a portion of the population. However, some Jews remained. For the two millennia after the Roman conquest, no other state or unique groups developed in the region. Instead, different empires and people came, colonized, ruled, and disappeared. Jews remained in Palestine during these changes.

Throughout these 2,000 years, Jews, regardless of their current country of residence, continued to view a return to their ancient homeland as an essential part of their identity and a source of hope. Between 1517 and 1917, Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire. The region initially prospered under the Ottomans, but during the Empire’s decline, it was reduced to a sparsely populated, impoverished, barren area. Meanwhile, the Zionist movement was emerging in Europe in the late nineteenth century, generated by increasing antisemitism and violence against Jews in Europe as well as the rising nationalism throughout the continent. The Zionists, whose goal was the return of the Jewish people to a sovereign state in the Land of Israel, fostered increased Jewish immigration to Palestine and sought international political recognition of the Jewish right to independence in Palestine. When the Ottoman Empire was defeated in World War I (1914–1918), its lands were ceded to the victorious Allies who carved the land into new nations, which included Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria.

The British Mandate: Under the Treaty of Sèvres (1920), the League of Nations formally gave control of Palestine to the British government. Britain’s job was to implement the Balfour Declaration, which had been signed five years earlier, stating Britain’s desire to create a homeland in Palestine for the Jews. Even before this declaration, Jews had begun to purchase land and settle in the country. As they continued to do so, the Jewish population grew to some 600,000 on the eve of World War II.

Of course, when the modern return of Jews to the Land of Israel began, Arabs were living there. Toward the end of the nineteenth century and more so in the early twentieth century, the national consciousness of these Arabs emerged as Palestinian nationalism and that nationalism aspired to independence. Thus, the Arab desire for independence clashed with the Jewish desire for return. British control over this territory lasted from 1923 to 1948, during which time the authorities were challenged by the demands of Zionists for Jewish self-government, and a growing Arab nationalist movement rejecting this Jewish presence and nationalist aspirations.

Growing Jewish-Arab violence and attacks on British personnel by some Jewish extremists led Britain to announce that it sought to end its mandate of the area. During this period, there was also the 1939 “White Paper” that stated that Palestine would be neither a Jewish state nor an Arab state, but an independent state to be established within ten years. The “White Paper” also limited Jewish immigration to Palestine to 75,000 for the first five years, subject to the country’s ability to absorb them economically, and would later be contingent on Arab consent. Stringent restrictions were also placed on how much land Jews could acquire. Despite efforts to rescind the “White Paper” following the end of World War II, it remained in effect until the British departed Palestine in May 1948.

United Nations Partition Plan: Following Britain’s February 1947 announcement of its intention to terminate its mandate government, the UN General Assembly appointed a special committee—the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP)—to make recommendations on the land’s future government. UNSCOP recommended the establishment of two separate states, Jewish and Arab, to be joined by an economic union, with the Jerusalem-Bethlehem region as an enclave under international administration. On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly voted on the partition plan, adopted by 33 votes to 13 with 10 abstentions. The Jewish side accepted the UN plan for the establishment of two states. The Arab states rejected the plan and almost immediately formed volunteer armies that infiltrated Palestine against the Jews.

Founding of the State of Israel 1948: Israel’s establishment as an independent sovereign state was officially declared in Tel Aviv on Friday, May 14, 1948, by Zionist leader David Ben-Gurion, the day the British Mandate over Palestine was officially terminated, by UN Resolution 181.

War of Independence (1948–1949): When the UN voted to partition the Mandate on November 29, 1947, Palestinian Arabs, with the help of Arab states, launched attacks against Israel to seize the entire Mandate. On May 14, 1948, Israel declared independence and was immediately invaded by the armies of five Arab nations: Egypt, Syria, Transjordan, Lebanon, and Iraq. The newly formed Israeli Defense Force (IDF) managed to prevail after fifteen months of war.

The Six-Day War (1967): Israel was forced to defend itself when Syria, Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq intensified their attacks and Egypt illegally blocked Israel’s access to international waters and expelled UN peacekeeping forces. Four Arab countries mobilized more than 250,000 troops in preparation for a full-scale invasion. Israel preempted the invasion in a defensive war and managed to capture the West Bank from Jordan; Gaza and the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt; and the Golan Heights from Syria.

Israel Today: Since 1948, Israel’s population has grown tenfold. Israel was founded with a population of 806,000. Today there are 8.5 million Israelis; about 75% of them Jews. Like other democratic, multi-ethnic countries, Israel struggles with various social and religious issues and economic problems. It is a country of immigrants that often came to the country dispossessed.

On the political front, most Arab and Muslim states continue to deny the Jewish State’s right to exist. Unfortunately, only two of the twenty-two Middle Eastern states have signed peace agreements with Israel—Egypt, and Jordan. The ongoing Palestinian-Israeli conflict is complex, with challenges related to borders, settlements, sovereignty, and other contentious issues. There are those on both sides of the conflict who hope one day to achieve a peaceful coexistence.

Location: Israel is located at the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea, where Europe, Africa, and Asia meet. The country borders Lebanon and Syria in the north, Jordan to the east, and Egypt to the south.

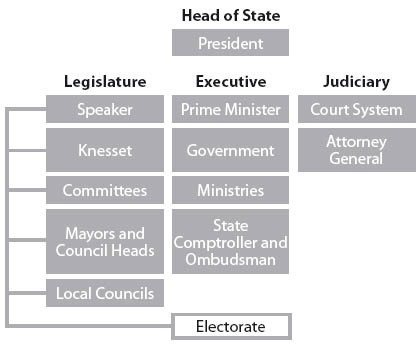

Hierarchy Structure of Israel

Israel is a parliamentary democracy consisting of legislative, executive, and judicial branches. Its institutions are the presidency, the Knesset (parliament), the government (cabinet of ministers), and the judiciary.

The system is based on the principle of separation of powers, in which the executive branch (the government) is subject to the confidence of the legislative branch (the Knesset) and the independence of the judiciary is guaranteed by law.

Israel is a parliamentary democracy with a hierarchical structure that includes several levels of government and authority. The hierarchy is as follows:

Prime Minister: The Prime Minister is the head of the Israeli government and holds the highest executive authority. They are usually the leader of the political party or coalition that holds the majority of seats in the Knesset (the Israeli parliament). The Prime Minister is responsible for forming a government, making policy decisions, and representing Israel internationally.

Cabinet: The Cabinet is composed of government ministers, each responsible for a specific government department or portfolio (such as defense, finance, foreign affairs, etc.). The Cabinet is headed by the Prime Minister and collectively makes important policy decisions.

Knesset: The Knesset is the unicameral parliament of Israel. It is composed of 120 members (known as Knesset members or MKs) who are elected through proportional representation. The Knesset passes laws, approves the national budget, and exercises legislative oversight over the government’s activities.

President: The President of Israel is a largely ceremonial role, serving as the head of state. The President’s duties include representing the country at official events, receiving foreign dignitaries, and granting pardons based on the recommendation of the Justice Minister.

Supreme Court: The Supreme Court of Israel is the highest judicial authority in the country. It serves as a court of appeals for lower courts and has the authority to hear cases related to constitutional matters and administrative decisions. The Court also plays a role in safeguarding democratic principles and human rights in Israel.

Districts: Israel is divided into six administrative districts, each headed by a District Commissioner. These districts are further divided into municipalities and local councils. Local governments have varying degrees of autonomy and responsibility for issues like education, local planning, and public services.

Local Authorities: Israel has various local authorities, including municipalities and local councils. These entities are responsible for managing local affairs, infrastructure, and services within their jurisdictions.

Israel Constitutions

Israel has no written constitution. Various attempts to draft the formal document since 1948 have fallen short of the mark, and instead, Israel has evolved a system of basic laws and rights, which enjoy semi-constitutional status. This provisional solution is increasingly inadequate for Israel’s needs, and the necessity for completing this historic task has never been so urgent.

In May 2003, the Constitution, Law, and Justice Committee of the Knesset, chaired by Member of Knesset Michael Eitan, initiated the Constitution by Broad Consensus Project, which aims to write a constitution for the State of Israel. The Committee has been meeting weekly since then to consolidate a draft of a constitution that will enjoy wide support among Israelis and Jews worldwide. The proposed constitution will ultimately be brought to the Knesset and the people for consideration and ratification.

The Committee believes that since Israel is the democratic state of the Jewish people, it is appropriate to appeal to the worldwide Jewish community and invite their input on central constitutional issues, particularly regarding those questions which involve the relationship between Israel and the Jewish people.

Israel does not have a formal written constitution in the traditional sense. Instead, it has a collection of Basic Laws that serve as constitutional provisions. These Basic Laws cover various aspects of governance, rights, and institutions. Amendments to these Basic Laws require a special majority in the Knesset (Israeli parliament). Some notable amendments include:

Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty (1992): This Basic Law guarantees fundamental rights to all individuals in Israel, including the right to life, privacy, and freedom of expression. While not an amendment per se, its enactment was a significant step in strengthening constitutional protections.

Basic Law: Freedom of Occupation (1994): This Basic Law ensures the right to work and pursue a chosen occupation. It emphasizes the importance of maintaining individual rights within the framework of a democratic society.

Basic Law: The Knesset (1992, amended multiple times): This Basic Law outlines the structure, functions, and powers of the Knesset, Israel’s parliament. Amendments to this law have addressed issues such as the disqualification of candidates and parties that deny Israel’s existence as a Jewish and democratic state.

Basic Law: Government (2001): This Basic Law details the structure and powers of the government, including the role of the Prime Minister and ministers. It also regulates matters related to the formation and dissolution of the government.

Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel (1980): This Basic Law declares Jerusalem as the united capital of Israel. While not specifically amended, its status and implications have been a subject of international debate and contention.

Basic Law: Referendum (2014): This Basic Law outlines the circumstances under which certain significant decisions, such as territorial changes involving areas under Israeli sovereignty, would require approval through a national referendum.

Federal Government

Executive Authority: The executive authority of the state is the government (cabinet of ministers), charged with administering internal and foreign affairs, including security matters. Its policy-making powers are very wide, and it is authorized to take action on any issue which is not legally incumbent upon another authority.

The cabinet determines it working the formation of a government, a list of ministers for Knesset approval, together with an outline of proposed government guidelines. All the ministers must be Israeli citizens and residents of Israel and all must be Knesset members.

Once approved, the ministers are responsible to the prime minister for the fulfillment of their duties and accountable to the Knesset for their actions. Most ministers are assigned a portfolio and head a ministry; ministers who function without a portfolio may be called upon to assume responsibility for special projects. The prime minister may also serve as a minister with a specific portfolio.

Ministers, with the approval of the prime minister and the government, may appoint a deputy minister in their ministry; all must be Knesset members.

Like the Knesset, the government usually serves for four years, but its term may be shortened by the resignation, incapacitation, or death of the prime minister or a vote of no-confidence by the Knesset.

If the prime minister is unable to continue in office due to death, incapacitation, resignation, or impeachment, the government appoints one of its members (and decision-making procedures. It usually meets once a week, but additional meetings may be called as needed. It may also act through ministerial committees.

Forming a government: All governments to date have been based on coalitions of several parties since no party has ever received enough Knesset seats to form a government by itself.

Following consultations, the president presents one Knesset member with the responsibility of forming a government. To do so, this Knesset member has to present, within 28 days of being given responsibility for must be a Knesset member) as acting prime minister.

In case of a vote of no-confidence, the government and the prime minister remain in their positions until a new government is formed.

Legislature branch: The Knesset (Israel’s unicameral parliament) is the country’s legislative body.

The Knesset (Israel’s unicameral parliament) is the country’s legislative body. The Knesset took its name and fixed its membership at 120 from the Knesset Hagedolah (Great Assembly), the representative Jewish council convened in Jerusalem by Ezra and Nehemiah in the 5th century BCE.

A new Knesset begins to function after general elections, which determine its composition. In the first session, Knesset members declare their allegiance, and the Knesset speaker and deputy speakers are elected. The Knesset usually serves for four years but may dissolve itself or be dissolved by the prime minister at any time during its term. Until a new Knesset is formally constituted following elections, full authority remains with the outgoing one.

The Knesset operates in plenary sessions and through 15 standing committees. In plenary sessions, general debates are conducted on legislation submitted by the government or by individual Knesset members, as well as on government policy and activity. Debates are conducted in Hebrew, but members may speak Arabic, as both are official languages. Simultaneous translation is available.

To become law, a regular state bill must pass three readings in the Knesset (while private bills have four readings). In the first reading, the bill is presented to the plenary, followed by a short debate on its contents, after which it is referred to the appropriate Knesset committee for detailed discussion and redrafting, if necessary. When the committee has completed its work, the bill is returned to the plenary for its second reading, at which time committee members who have reservations may present them to the plenary. Following a general debate, each article of the bill is put to a vote and, unless it is necessary to return it to committee, the third reading takes place immediately, and a vote is taken on the bill as a whole. If the bill passes, it is signed by the presiding speaker and is later published in the Official Gazette, with the signatures of the president, prime minister, Knesset speaker, and the minister responsible for the law’s implementation. Finally, the state seal is affixed to it by the minister of justice, and the bill becomes law.

Judiciary: The independence of the judiciary is guaranteed by law. Judges are appointed by the president, upon recommendation of a nominations committee comprised of Supreme Court judges, members of the bar, and public figures. Appointments are permanent, with mandatory retirement at age 70.

Special Courts (1 judge): Traffic, labor, juvenile, military, and municipal courts, with clearly defined jurisdiction; administrative tribunals.

Religious Courts (1 or 3 judges): Jurisdiction in matters of personal status (marriage, divorce, maintenance, guardianship, adoption) vested in judicial institutions of the respective religious communities: Jewish rabbinical courts, Muslim sharia courts, Druze religious courts, ecclesiastical courts of the ten recognized Christian communities in Israel.

Magistrates’ Court (1 judge): Civil and minor criminal offenses; jurisdiction in civil and criminal cases.

District Court (1 or 3 judges): Appellate jurisdiction over magistrates’ courts; original jurisdiction in more important civil and criminal cases.

Supreme Court (1, 3, 5 or a larger uneven number of judges): Ultimate appellate jurisdiction nationwide; right to address issues when necessary to intervene for the sake of justice; authority to release persons illegally detained or imprisoned; sitting as a High Court of Justice, hears petitions against any government body or agent and is the court of first and last instance.

Local Government

Services provided by local government include education, culture, health, social welfare, road maintenance, public parks, water, and sanitation. Each local authority functions through by-laws complementing national laws, which have been approved by the Ministry of the Interior. Some authorities operate special courts in which transgressors of local by-laws are tried. Financing for local authorities comes from local taxes, as well as allocations from the state budget. Every authority has a comptroller who prepares an annual report.

The law recognizes three types of local authorities: municipalities, which provide the framework for urban centers with populations of over 20,000; local councils, which manage towns with populations of between 2,000 and 20,000; and regional councils, which are responsible for several villages grouped within a certain radius.

Each local authority is administered by a mayor or chairperson and a council. The number of council members is determined by the Ministry of the Interior, according to the authority’s population. Currently, there are 73 municipalities, 124 local councils, and 54 regional councils.

All municipalities and local councils are united, voluntarily, in a central body, the Union of Local Authorities, which represents them before the government, monitors relevant legislation in the Knesset and provides guidance on issues such as work agreements and legal affairs. Affiliated with the International Association of Municipalities, the union maintains ties with similar organizations throughout the world and arranges twin cities programs and exchanges of international delegations.

Elections

Elections are general, national, direct, equal, secret, and proportional. The entire country constitutes a single electoral constituency, and all citizens are eligible to vote from age 18. On Election Day, voters cast a ballot for a political party to represent them in the Knesset.

Election Day is a national holiday, free transportation is available to voters who happen to be outside their polling district on that day and polling stations are provided for military personnel, hospital patients, and prisoners, as well as for merchant seamen and Israelis on official assignment abroad.

The Central Elections Committee, headed by a justice of the Supreme Court and including representatives of the parties holding Knesset seats, is responsible for conducting the elections. Regional election committees oversee the proper functioning of local polling committees, which include representatives of at least three parties in the outgoing Knesset.

In each election to date, between 77 and 90 percent of all registered voters have cast their ballots, expressing the great interest taken by most Israelis in their national and local politics.

Knesset elections are based on a vote for a party rather than for individuals, and the many political parties that run for the Knesset reflect a wide range of outlooks and beliefs.

Local Elections: Elections for local government are conducted by secret ballot every five years. All permanent residents, whether Israeli citizens or not, are eligible to vote in local elections from age 17 and to be elected from age 21. In elections for municipal and local councils, ballots are cast for a party list of candidates, with the number of council seats attained by each list proportional to the percentage of votes received. Mayors and chairpersons of local councils are elected directly.

In regional council elections, one candidate from each village is elected by a simple plurality, with those elected becoming members of the council. Heads of regional councils are selected from among the regional council’s members.

Local elections are financed by government appropriations, based on the number of mandates that each faction or list wins in the local authority.

Political Parties: Israel has a dynamic political landscape with a range of parties representing diverse ideologies and interests. Some of the major political parties active at that time include:

Likud Party: The Likud Party started as a group of parties that united in 1973 just before the elections to the 8th Knesset and included Herut, the Liberal Party, the Free Center, the National List, and the Labor Movement for Greater Israel. A right-wing party and one of the largest in Israel, Likud is associated with conservative and nationalist positions. It has been traditionally supportive of security and defense policies and has been in power for various periods.

Blue and White Party: Blue and White is a centrist electoral list established in the run-up to the 2019 elections. It includes the Israel Resilience Party, Telem, and Yesh Atid. The former two (headed by Benny Ganz and Moshe Ya’alon respectively) were formed in late 2018 and decided to run together. Following intensive efforts, Yesh Atid’s leader Yair Lapid also decided to head his party into the list. Blue and White is a Zionist Liberal party located in the center of the political map. Formed as a centrist alliance, the party aimed to offer an alternative to Likud’s dominance. It emphasized issues like security, economic stability, and social unity. Blue and White dissolved after internal disagreements, and its members returned to their original parties.

Yesh Atid: A centrist party focused on socio-economic issues, Yesh Atid advocates for reducing the cost of living, promoting education, and creating a more equitable society. Yesh Atid became the first Israeli political party to form an “Anglo women’s division” on February 29, 2016, to attract new voters. The Anglo women’s division will focus on women’s issues and female representation in government.

Shas: Shas was founded by ultra-Orthodox Sephardic Jews in response to their sense that they were at an institutional disadvantage and were under-represented in Israeli politics in comparison to Ashkenazi Haredim. With the establishment of Shas on the national level, the Council of Torah Sages, headed by Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, was also established. Rabbi Menachem Shach, the head of the Lithuanian (non-Hasidic) ultra-Orthodox community, and Rabbi Yosef served as the Council’s highest decision-makers. After 1990, Rabbi Shach resigned from this position, leaving Rabbi Ovadia Yosef as the sole spiritual leader of the Shas party. A religious party primarily representing Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews, Shas focuses on issues important to the religious community, such as religious education, family values, and social welfare.

United Torah Judaism: United Torah Judaism (UTJ) promotes the interests of the Haredi community in Israel in the areas of education and welfare and regarding specific issues such as army service. It also works to preserve the religious character of the State of Israel. In September 1999, during the 15th Knesset, United Torah Judaism even left the coalition in protest against the shipment of a turbine to the Ashkelon power station on the Jewish Sabbath. Regarding foreign policy and security, United Torah Judaism is a centrist party, which determines its positions based on religious concerns more than security concerns or diplomatic considerations Another religious party, United Torah Judaism, represents the Ashkenazi Haredi community. It also prioritizes religious matters and preserving the traditional way of life.

Immigration System of Israel

- Immigration Overview

- Types of Immigration

- Asylum

- The Asylum Process

Israel Immigration Overview

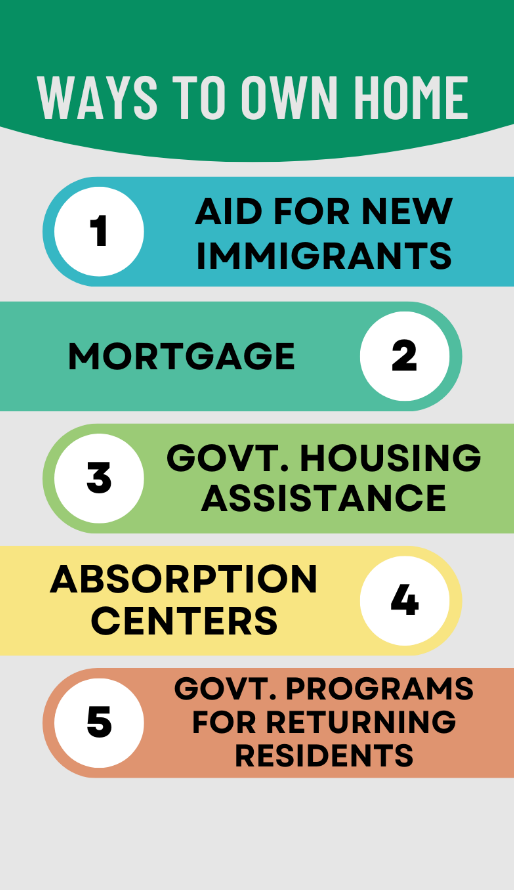

Immigrating to Israel, a country with a rich history and diverse culture is facilitated through various pathways, including the unique Law of Return for Jews worldwide, family reunification, employment opportunities, and educational pursuits. New immigrants often benefit from financial support, language courses, and housing assistance to ease their transition. Israel offers a dynamic environment for skilled professionals, particularly in the technology and innovation sectors.

However, prospective immigrants should be prepared for cultural adaptation and navigate the complexities of the region’s political and security landscape. Israel’s immigration policies evolve, so it’s crucial to consult official sources for the latest information when considering this vibrant and multifaceted destination for immigration.

Legal immigration: Legal immigration to Israel primarily occurs through various established channels, including Aliyah (Jewish immigration), family reunification, employment-based visas, student visas, and tourist visas. Under the Law of Return, Jews from around the world have the right to immigrate to Israel. Family members of Israeli citizens or residents can reunify with their loved ones, while those with job offers can obtain work visas. Students accepted by Israeli educational institutions can apply for student visas, and tourists can enter the country with tourist visas.

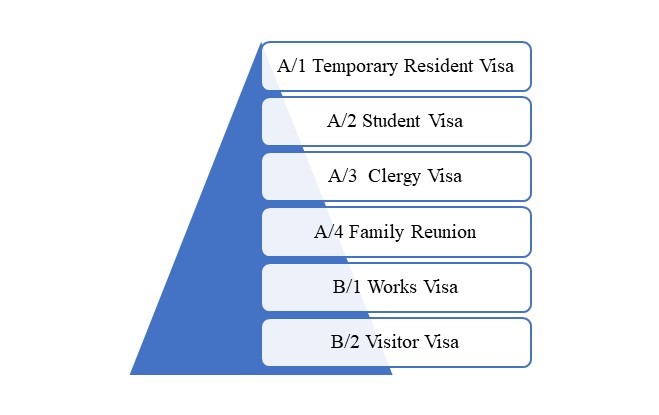

Visa Categories: Israel provides a range of visa categories tailored to diverse immigration and travel purposes. The primary options encompass Tourist Visas for short-term visitors, Student Visas for international students, Work Visas for foreign employees with job offers, Family Reunification Visas facilitating the reunion of immediate family members with Israeli citizens or residents, Temporary Resident Visas for those intending to establish long-term residency, and the unique Aliyah Visa, which is exclusively available to Jewish immigrants under the Law of Return, offering substantial support and integration services.

Naturalization: Naturalization in Israel refers to the process through which foreign nationals can become Israeli citizens. To be eligible for naturalization, individuals typically need to meet certain residency requirements, demonstrate proficiency in Hebrew, and pass a citizenship test on Israeli culture, history, and the legal system. Additionally, they must pledge allegiance to the State of Israel and renounce any other citizenship they hold, as Israel generally does not allow dual citizenship.

Application process: The immigration application process to Israel typically begins with determining your eligibility for one of the available immigration categories, such as Aliyah (for Jewish immigrants), family reunification, work, or student visas. You will need to gather and submit the required documents, which may include proof of Jewish heritage for Aliyah or family relationship documents for family reunification. After submitting your application, there may be interviews and additional documentation requests. If approved, you’ll receive the appropriate visa, which comes with its own set of benefits and requirements.

Importance of legal assistance: Legal assistance is of paramount importance for immigration to Israel due to the complex and evolving nature of immigration laws and regulations. Navigating the intricacies of Israeli immigration requires expert guidance to ensure applicants meet eligibility criteria, compile necessary documentation, and adhere to legal procedures. Immigration lawyers play a crucial role in helping individuals and families understand their rights and options, completing application forms, and representing clients before Israeli immigration authorities.

Rights and responsibilities: Immigrating to Israel comes with both rights and responsibilities. Immigrants, especially those who become Israeli citizens, enjoy a range of rights, including access to social services, education, healthcare, and employment opportunities. They have the right to vote and participate in the democratic process, as well as the freedom to practice their religion and culture.

However, immigrants are also responsible for adhering to Israeli laws and regulations, including military service requirements for eligible citizens, paying taxes, and contributing to the country’s economic and social fabric. Additionally, integrating into Israeli society, learning Hebrew, and respecting the nation’s diverse cultural norms are vital responsibilities for immigrants to foster a sense of belonging and coexistence within the country.

Resources and support: Immigration to Israel is supported by a range of resources and services designed to assist newcomers in their transition. Government agencies such as the Ministry of Aliyah and Integration provide financial aid, language courses, and housing support to eligible immigrants.

Nonprofit organizations like the Jewish Agency and Nefesh B’Nefesh offer guidance and practical assistance, helping newcomers navigate bureaucratic processes and find employment opportunities. Educational institutions and community centers also provide integration programs and social support to foster a sense of belonging.

These combined efforts aim to facilitate a smooth and successful transition for immigrants as they embrace Israel’s culture and opportunities.

Types of immigration

A/1 Temporary Resident Visa: The A/1 Temporary Resident Visa in Israel is a short-term visa category typically issued to foreign nationals seeking to immigrate under the Law of Return. It allows individuals who are eligible for Aliyah (Jewish immigration) to live and work in Israel temporarily while they complete the immigration process. This visa provides newcomers with an initial period of stay to begin their integration into Israeli society, which may include language courses and access to various support services. It’s an essential step in the immigration process for eligible individuals as it grants them legal status in Israel during their initial settlement period, allowing them to access various benefits and services as they transition to their new life in the country.

A/2 Student Visa: The A/2 Student Visa is a type of visa for individuals who wish to study in Israel. This visa allows foreign students to enroll in academic or vocational programs at recognized Israeli educational institutions. To obtain an A/2 Student Visa, applicants typically need to provide proof of acceptance from an Israeli educational institution and demonstrate sufficient financial means to support themselves during their studies. The visa is usually issued for the duration of the academic program, and students can extend it as needed. It’s important to note that while holding an A/2 Student Visa, individuals are generally not permitted to work in Israel unless they obtain a separate work permit.

A/3 Clergy Visa: The A/3 Clergy Visa is a specific type of visa for religious clergy members seeking to immigrate to Israel. This visa is designed to accommodate individuals planning to work in a religious capacity, such as priests, rabbis, or imams, within recognized religious institutions in Israel. To obtain an A/3 Clergy Visa, applicants typically need to provide documentation demonstrating their religious affiliation, a job offer from a recognized religious institution, and proof of their qualifications as clergy members. Once granted, this visa permits them to live and work in Israel temporarily, usually for the duration of their religious duties or assignments.

A/4 visa for spouses and children: A/4 visa for spouses and children is specifically designed for spouses and children of foreign workers or residents in the country. This visa allows them to join their family members who are already living and working in Israel. To qualify for the A/4 visa, applicants need to demonstrate their relationship to the Israeli resident or worker. Once obtained, this visa permits spouses and children to live, study, and work in Israel for the duration of the sponsoring family member’s stay. It’s crucial to note that the A/4 visa is tied to the principal applicant’s status, and if they leave Israel, the dependents’ visas may also be affected. Therefore, it’s essential to keep immigration authorities informed of any changes in the family’s situation or the principal applicant’s status to ensure legal compliance and uninterrupted residency.

B/1 work visa: The B/1 Work visa is a type of Israeli visa designed for foreign nationals seeking employment in Israel. To obtain a B/1 visa, applicants typically need a job offer from an Israeli employer. This visa allows individuals to work legally in Israel for a specific employer and is usually granted for a set period, often linked to the duration of the employment contract. B/1 visa holders are expected to abide by the terms of their employment and may be subject to renewal if they continue working for the same employer. It’s important to note that this visa does not grant permanent residency or citizenship.

B/2 visitor visa: The B/2 Visitor’s visa in Israel is designed for individuals who wish to temporarily visit the country for purposes such as tourism, business meetings, conferences, or short-term courses. It typically allows for stays of up to three months, but extensions may be possible in some cases. Unlike immigration visas like Aliyah, the B/2 visa does not grant the right to work or reside in Israel long-term. Applicants must provide documentation supporting the purpose of their visit, maintain sufficient financial means to cover their stay and return to their home country when the visa expires.

Asylum

Asylum is a legal protection and status granted by a government to individuals who have fled their home countries due to a well-founded fear of persecution based on factors such as race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group. The concept of asylum is rooted in international and domestic law, and it is designed to provide safety and refuge to those who are at risk of harm in their home countries. Here are the major elements and components of asylum:

Refugee Definition: To qualify for asylum, an individual must meet the legal definition of a refugee. This definition is typically based on international agreements, such as the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. According to these agreements, a refugee is someone who has a well-founded fear of persecution based on certain protected grounds, as mentioned earlier.

Persecution: Persecution refers to the serious and sustained harm or mistreatment that individuals face in their home country. It can take various forms, including physical violence, torture, discrimination, harassment, imprisonment, or threats to life or freedom.

Well-Founded Fear: To be eligible for asylum, an individual must demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution. This means that there must be a reasonable basis for believing that they would be at risk of harm if they were forced to return to their home country.

Protected Grounds: Asylum claims are typically based on one or more of the following protected grounds:

Race: Persecution based on a person’s race, ethnicity, or skin color.

Religion: Persecution based on a person’s religious beliefs or practices.

Nationality: Persecution based on a person’s nationality or membership in a particular ethnic or national group.

Political Opinion: Persecution of individuals with specific political beliefs or affiliations.

Membership in a Particular Social Group: Persecution of individuals due to their membership in a specific social group, which can be defined in various ways, including gender, sexual orientation, or other characteristics.

Application Process: Asylum seekers must follow a formal application process in the host country. This typically involves submitting an asylum application, attending interviews with immigration authorities, and providing evidence to support their claim.

Non-Refoulement: One of the fundamental principles of asylum is the principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits the deportation or return of asylum seekers to a country where they would face persecution. This principle is enshrined in international law.

Legal Rights and Protections: Asylum seekers are entitled to certain legal rights and protections during the asylum process. These may include access to legal counsel, the right to work, access to healthcare and education, and freedom from detention in some cases.

Status Determination: Immigration or asylum authorities in the host country are responsible for determining whether an individual qualifies for refugee status. This process involves evaluating the credibility of the asylum seeker’s claim and assessing the level of risk they face in their home country.

Appeals Process: If an asylum claim is denied, many countries provide an appeals process that allows applicants to challenge the decision. This process may involve presenting additional evidence or legal arguments.

Resettlement: In some cases, if an individual is granted asylum, they may have the option to apply for resettlement in a third country if they are unable to return to their home country or integrate into the host country.

Asylum is a critical mechanism for protecting the rights and safety of individuals who are forced to flee their countries due to persecution. It is governed by a complex framework of international and domestic laws and regulations, which can vary from one country to another.

The Asylum Process

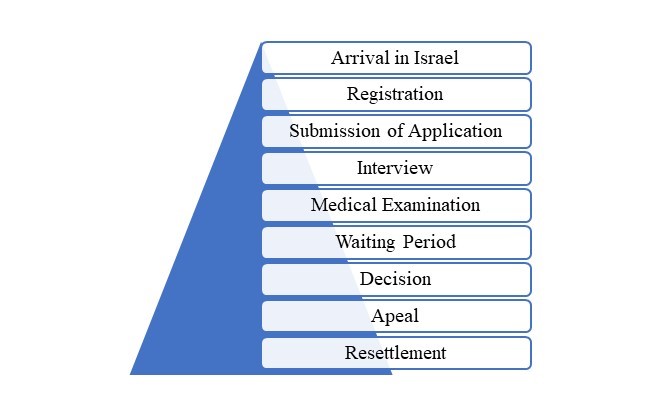

Seeking asylum in Israel involves a detailed legal process designed to assess an individual’s eligibility for refugee status. Here is a brief overview of the steps involved:

Arrival in Israel: Asylum seekers typically arrive in Israel on tourist visas or other means. They must be physically present in Israel to start the asylum application process. Arrival in Israel as a process of seeking asylum involves several crucial steps. Asylum seekers typically arrive in Israel, often through irregular channels or crossing the border, fleeing persecution, conflict, or other life-threatening circumstances in their home countries. Upon arrival, they may be detained temporarily for security and administrative purposes, and their identity and background are screened.

Registration: Registering at the Population and Immigration Authority (PIBA) as part of the asylum-seeking process in Israel is a crucial step for individuals fleeing persecution and seeking refuge. To initiate their asylum claim, individuals must first arrive in Israel and approach PIBA’s offices. There, they undergo an initial registration process, during which they provide personal information, background details, and the reasons for seeking asylum. This information helps PIBA assess their eligibility for refugee status under international and Israeli law. Upon arrival in Israel, asylum seekers should report to the Population and Immigration Authority (PIBA) to register their presence in the country. Failure to do so may result in detention or deportation.

Submission of Asylum Application: Asylum seekers can formally apply for asylum by applying to the Ministry of Interior’s Refugee Status Determination (RSD) unit. This unit is responsible for processing asylum claims.

You can Complete and submit the Refugee status determination application online. After the submission of the application, you will get an email confirmation to the email you provided on your application. This is not confirmation that your application has been submitted. You will be scheduled an appointment to confirm your details in person with the Border Control Officer in Charge at the enforcement facility in Bnei Brak. After confirming your details in person at the enforcement facility, you will be referred for further handling which will include an interview

Interview: After applying, applicants will undergo an interview with immigration officials. During this interview, they will be asked to provide detailed information about their reasons for seeking asylum and their experiences in their home country. During the asylum interview, the asylum seeker meets with an immigration officer or caseworker from PIBA. The interview is a crucial opportunity for the applicant to present their case for asylum.

Documentation: Asylum seekers are encouraged to provide any evidence, documents, or witnesses that support their claim. This could include personal testimonies, medical records, photographs, or other relevant materials.

Reasons for Asylum: The applicant must explain in detail why they are seeking asylum in Israel. This typically involves recounting the persecution, threats, or violence they faced in their home country. Asylum seekers should demonstrate that they fear returning to their country of origin due to a well-founded fear of persecution based on factors like race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.

Language Barrier: Language can sometimes be a barrier during the interview, especially if the asylum seeker does not speak Hebrew or English fluently. In such cases, interpreters may be provided to ensure clear communication.

Medical Examination: Applicants may also undergo a medical examination to document any injuries or trauma they have suffered that can serve as evidence of persecution.

Waiting Period: After submitting the application and undergoing the interview, asylum seekers may need to wait for a decision on their case. This waiting period can vary in length.

Decision: The RSD unit will evaluate the asylum claim and determine whether the applicant meets the criteria for refugee status under Israeli law. If approved, the applicant will be recognized as a refugee and granted asylum status.

Appeals: If the asylum application is denied, applicants have the right to appeal the decision within a specified timeframe. The appeal process involves presenting additional evidence or arguments to support their claim.

Resettlement or Temporary Protection: If an asylum claim is approved, the applicant will be granted refugee status, which may include certain rights and protections. Israel provides some assistance to refugees but does not grant them permanent residency or citizenship.

If your application is approved, you will be issued a permit by the asylum seeker handling process

Required Documents

- You must attach a clear, readable copy of your passport.

- You must provide your full contact details, including an email and telephone number.

- If you are in a holding facility you need to apply through the facility administration.

If you do not complete the application correctly, it will be denied.

Highlights

- Complete the application in English

- Make sure to include detailed information and answers to questions about your application for asylum

- Make sure your answers are in the correct fields on the online application

- Only use the online application to apply. Do not use the paper application form

- You must attend your meeting at the enforcement facility in Bnei Brak. If you do not, you will lose your right to apply for asylum.

- If you do not have an appointment, you will not be permitted to enter the Bnei Brak Population and Immigration Authority.

- Due to the coronavirus outbreak, you must wear a face mask that covers your mouth and nose. You will not be permitted to enter without a face mask, by Public Health Order (Novel Coronavirus)

- Applications made by unaccompanied minors, those suffering from mental health disorders, or victims of torture, will be handled with particular attention, care, and sensitivity to the circumstances.

It’s important to note that Israel’s asylum policies have been subject to controversy and change over the years, and the government has taken various measures to deter irregular migration. Therefore, asylum seekers should seek legal counsel or assistance from organizations that specialize in refugee and asylum issues to navigate the process effectively and understand the most current policies and procedures. Additionally, the asylum process can be time-consuming, and applicants may face challenges during the waiting period, including issues related to housing, employment, and access to services.

Financial System of Israel

- Overview of Israel

- Financial System

- Banking System

- Capital Market

- Insurance System

- Investment Funds

- Regulatory Authorities

- Financial Technology

Overview of the financial system

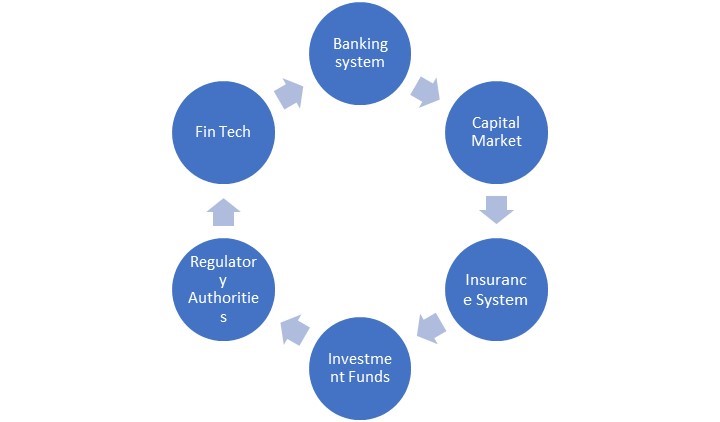

The financial system refers to the comprehensive network of institutions, markets, regulations, and mechanisms that facilitate the flow of funds and financial resources within an economy. It plays a fundamental role in supporting economic activities by efficiently channeling savings into investments, facilitating transactions, managing risks, and promoting economic growth.

The key components of a country’s financial system include banks, financial markets (such as stock and bond markets), insurance companies, pension funds, regulatory authorities, and various financial intermediaries. The financial system also encompasses the legal and regulatory framework that governs financial transactions and activities, ensuring transparency, stability, and the protection of investors and consumers. Overall, a well-functioning financial system is critical for the efficient allocation of capital, economic development, and the stability of a nation’s economy.

Israel’s financial system is a robust and well-regulated network of institutions and markets that facilitate the flow of capital and financial services within the country. It comprises commercial banks, investment banks, a stock exchange (Tel Aviv Stock Exchange), and a bond market, along with insurance companies and pension funds. The central regulatory authority is the Bank of Israel, responsible for monetary policy and banking supervision. Additionally, the Ministry of Finance oversees fiscal policies and taxation. Israel’s financial system is bolstered by a thriving FinTech sector, and its currency, the New Israeli Shekel (NIS), plays a pivotal role in international trade. This financial system is crucial in supporting the nation’s dynamic and innovation-driven economy while ensuring stability and investor protection.

Banking System

Israel’s banking sector is a significant component of the country’s financial system, providing a wide range of financial services to both individuals and businesses. The sector is characterized by various types of banks, each serving specific purposes and customer segments. Here are the main types of banks in Israel’s banking sector:

Commercial Banks: There are two categories mentioned below that come under the umbrella of commercial banks:

Retail Banks: These banks serve individual consumers and offer a broad range of retail banking services, including savings and checking accounts, personal loans, mortgages, credit cards, and financial advisory services. Some of the major retail banks in Israel include Bank Hapoalim, Bank Leumi, Mizrahi Tefahot Bank, and First International Bank of Israel (FIBI).

Corporate Banks: Corporate or business banks primarily cater to the financial needs of large corporations, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and institutional clients. They provide corporate lending, trade finance, treasury services, and cash management services. The major commercial banks also have dedicated corporate banking divisions.

Investment Banks: Investment banks in Israel focus on providing specialized financial services related to capital markets and investment banking. These services may include asset management, underwriting of securities (such as IPOs and bond issuances), mergers and acquisitions (M&A) advisory, and wealth management. Prominent investment banks in Israel include Psagot Investment House, Excellence Investment House, and Meitav Dash.

Savings and Cooperative Banks: These banks are typically smaller in size and often have a more community-oriented focus. They provide traditional banking services like savings accounts, loans, and mortgages. While they are less prevalent than commercial banks, they serve an important role in some regions of Israel.

Foreign Banks: Several foreign banks operate in Israel, providing banking services primarily to international clients and businesses. They often specialize in cross-border transactions, foreign exchange services, and trade finance for multinational corporations.

Online and Digital Banks: Israel has seen the emergence of digital and online banks that operate exclusively through digital channels, without physical branch networks. These banks offer a range of financial services, including checking and savings accounts, payment services, and mobile banking apps. They are designed to cater to tech-savvy consumers who prefer online banking. Examples include Bank Yahav, Bank Otsar Ha-Hayal, and Discount Bank’s “Super-Phon” service.

Development and Mortgage Banks: These banks focus on providing long-term financing for housing and real estate projects. They play a crucial role in the real estate market, particularly in funding residential development and providing mortgages to homebuyers. The Israel Mortgage & Real Estate Corporation (known as “Tosea” in Hebrew) is a notable example.

Central Bank: The Bank of Israel, the country’s central bank, regulates and oversees the entire banking sector. It controls monetary policy, manages foreign exchange reserves, and ensures the financial system’s stability.

The Israeli banking sector is well-regulated and stable, with strict supervision by the Bank of Israel and other relevant authorities to maintain the integrity of the financial system. The sector’s diversity and competition contribute to the overall health and innovation within Israel’s financial industry, supporting the country’s robust economy.

Capital Market

Israel’s capital market plays a crucial role in the country’s economy by facilitating the allocation of funds from investors to businesses and government entities. It consists of various financial instruments and markets where securities are bought and sold. Here’s an explanation of Israel’s capital market and its primary types:

Stock Market: The primary stock exchange in Israel is the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange (TASE). TASE is one of the largest stock exchanges in the Middle East. It provides a platform for the trading of equities (stocks) issued by publicly listed companies. Companies list their shares on TASE to raise capital by selling ownership stakes to investors. Investors can buy and sell these shares, and the stock market provides liquidity for these transactions. TASE has different segments, including the Tel Aviv 35 Index (TA-35), which includes the 35 largest companies by market capitalization on the exchange.

Bond Market: Israel’s bond market is robust and includes both corporate and government bonds. Government bonds issued by the Israeli government are known as Israel Government Bonds (IGBs). Corporate bonds are issued by private companies to raise capital. These bonds pay interest to bondholders, and their value can fluctuate based on market conditions. IGBs are considered relatively safe investments and are often used by both domestic and international investors for income and capital preservation.

Derivatives Market: TASE also operates a derivatives market where investors can trade options and futures contracts. Derivatives are financial instruments whose value is derived from an underlying asset, such as a stock or an index. Options and futures contracts can be used for hedging against price fluctuations, speculation, and portfolio management.

Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs): Israel has a growing market for Real Estate Investment Trusts, or REITs. These are investment vehicles that allow individuals and institutions to invest in a diversified portfolio of real estate assets. REITs in Israel provide investors with exposure to income-producing real estate properties, such as commercial, residential, and industrial properties.

Private Equity and Venture Capital: While not part of the public capital market, private equity and venture capital are essential components of Israel’s overall financial ecosystem. Israel has a vibrant startup and technology sector, and private equity and venture capital firms play a significant role in funding and nurturing these companies.

Foreign Investment: Israel actively encourages foreign investment in its capital markets. Foreign investors can participate in the stock and bond markets, and the government offers various incentives and protections to attract foreign capital.

Regulation and Oversight: The capital market in Israel is regulated by the Israel Securities Authority (ISA), which ensures that market participants adhere to securities laws and regulations. The ISA aims to maintain market integrity, protect investors, and promote transparency in the capital market.

In summary, Israel’s capital market is a diverse and dynamic ecosystem comprising various types of financial instruments and markets. It serves as a critical source of financing for businesses, a means of investment for individuals and institutions, and a driver of economic growth and development in the country. The market is regulated to ensure fair and transparent operations while encouraging both domestic and foreign investment.

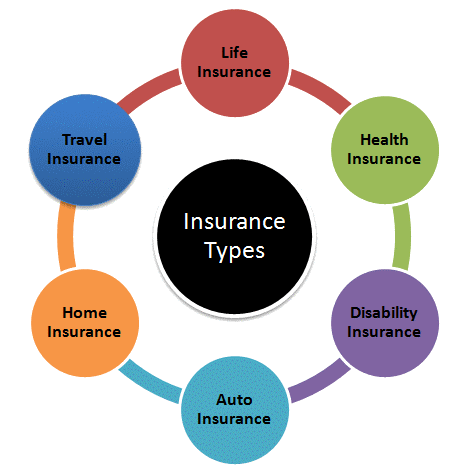

Insurance system

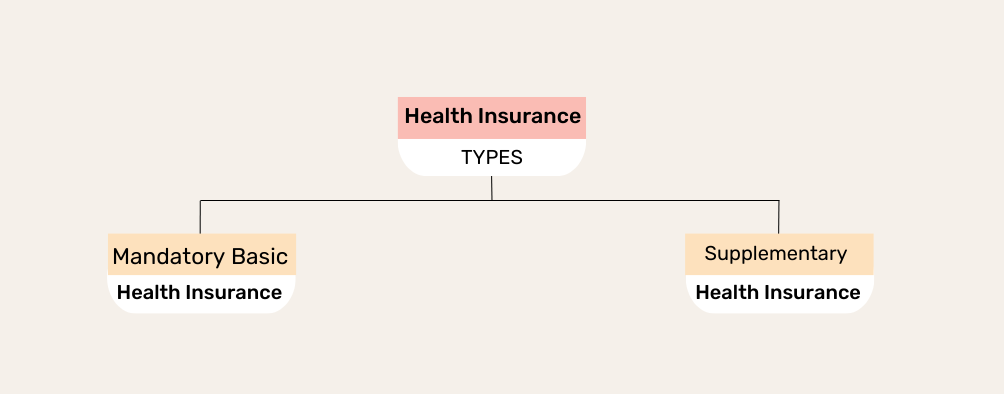

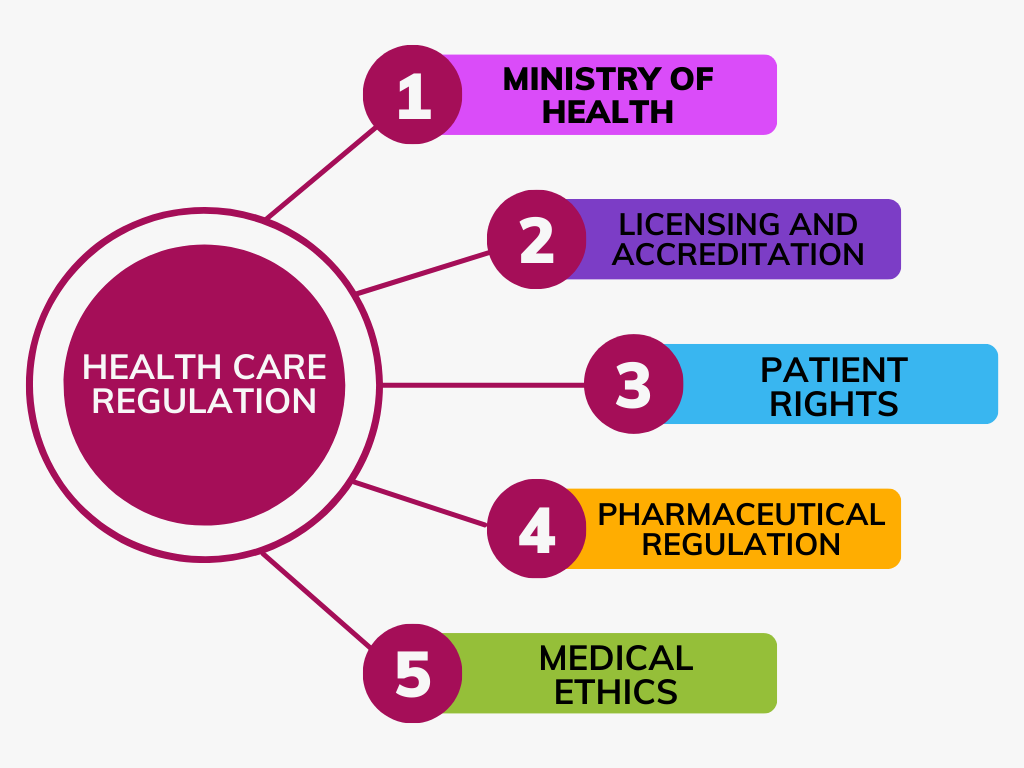

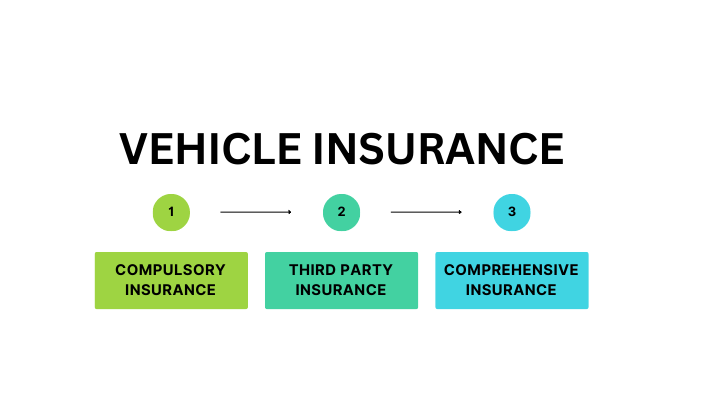

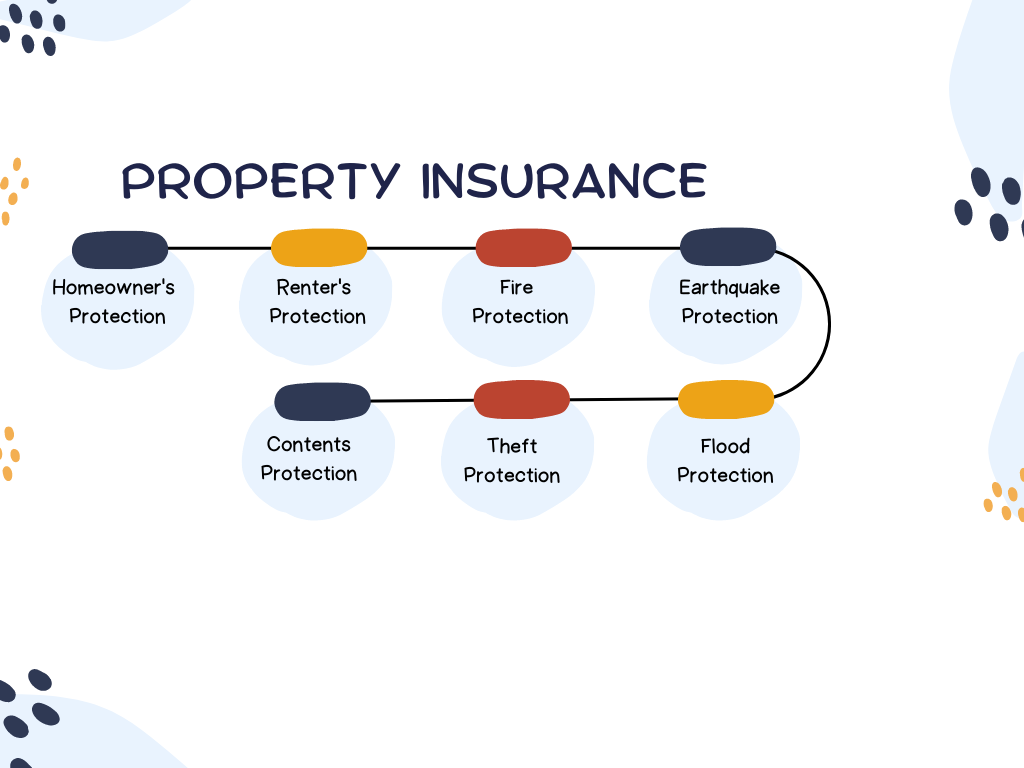

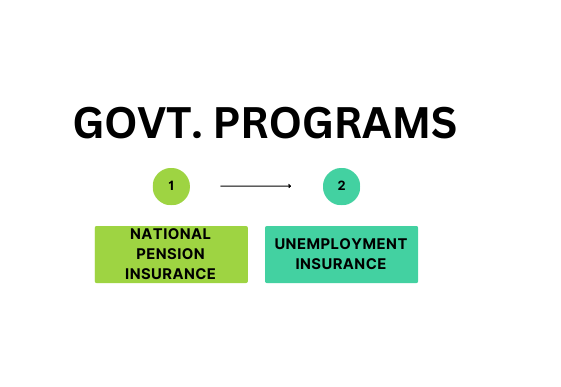

Israel has a well-developed insurance industry that provides various types of insurance coverage to individuals and businesses. Insurance in Israel is regulated by the Ministry of Finance and supervised by the Capital Market, Insurance, and Savings Authority. Here are some of the main types of insurance available in Israel:

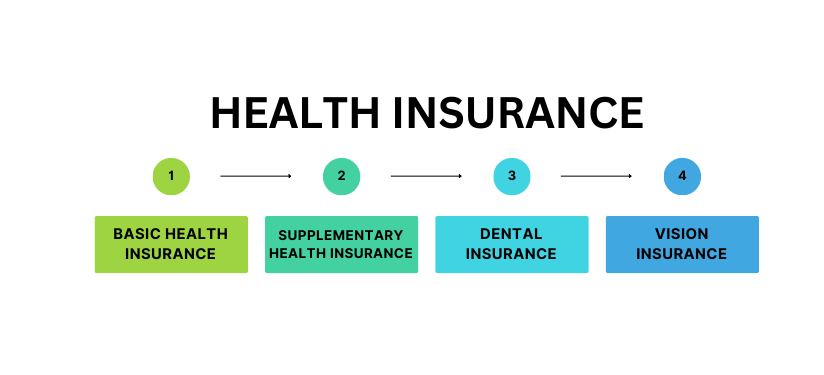

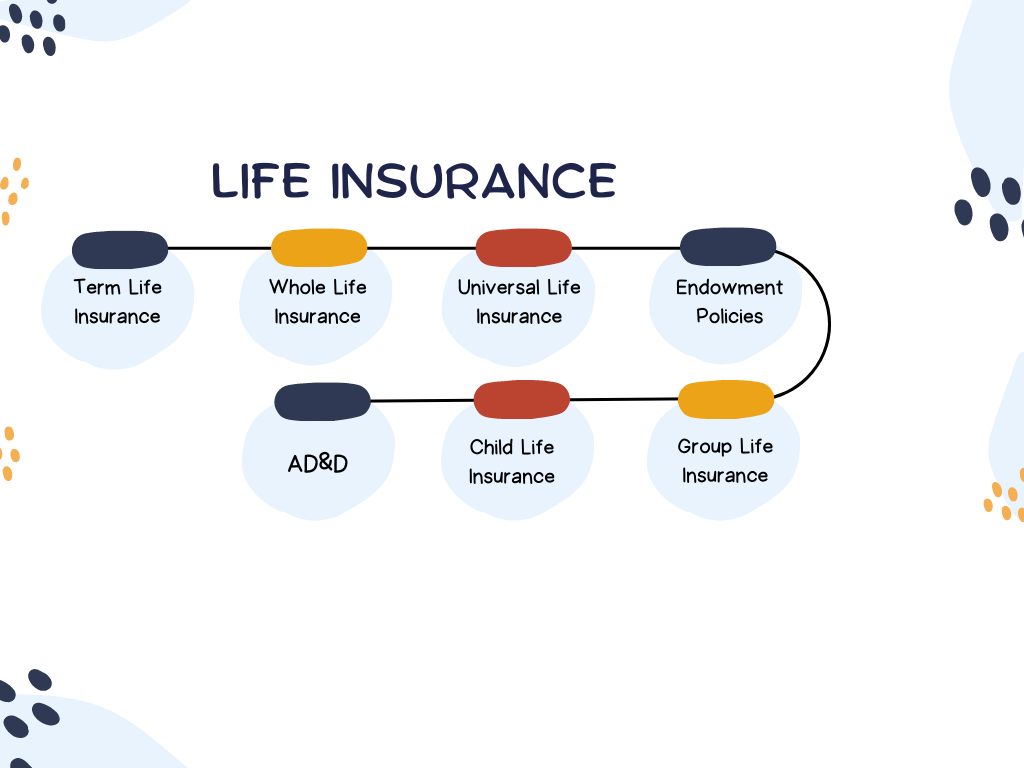

Life Insurance: Term life insurance provides coverage for a specified period, usually with a fixed premium for the duration of the policy. If the insured person passes away during the policy term, a death benefit is paid to the beneficiary. Whole life insurance offers coverage for the insured person’s entire life. It combines a death benefit with an investment component, allowing the policyholder to build cash value over time.

Non-Life Insurance: Property insurance covers damage or loss to physical assets, including homes, buildings, and personal belongings. It can also include coverage for fire, theft, natural disasters, and vandalism. Liability insurance protects against legal claims and lawsuits. This can include professional liability insurance, public liability insurance, and product liability insurance. Car insurance is mandatory in Israel and typically includes coverage for bodily injury, property damage, and theft. Additional coverage options, such as collision and comprehensive coverage, are also available. Travel insurance offers coverage for unexpected events while traveling, such as trip cancellations, medical emergencies, and lost luggage. While Israel has a universal healthcare system, private health insurance can provide additional coverage for services not covered by the public system, including faster access to specialists and elective procedures.

Workers’ Compensation Insurance: Employers in Israel are required to provide workers’ compensation insurance for their employees. This insurance covers medical expenses and wage replacement for employees who are injured or become ill as a result of their work.

Pension and Retirement Insurance: Pension insurance and retirement savings plans are essential for individuals planning for their retirement. These policies help individuals accumulate savings over their working years, which can then be used to provide income in retirement.

Credit Insurance: Credit insurance, also known as payment protection insurance, covers debt repayment in case of unexpected events, such as unemployment, disability, or death, which may prevent the insured person from making loan or credit card payments.

Marine and Aviation Insurance: These specialized insurance policies cover risks associated with shipping and aviation, including cargo insurance, hull insurance for ships and aircraft, and liability coverage for shipping and aviation-related businesses.

Cyber Insurance: With the increasing importance of digital technology, cyber insurance is becoming more prevalent. It provides coverage for losses and liabilities arising from cyberattacks, data breaches, and other cyber incidents.

Specialty Insurance: Some insurers offer specialty insurance products tailored to unique needs, such as kidnap and ransom insurance, event cancellation insurance, and insurance for high-value items like art and jewelry.

It’s important to note that insurance products and regulations may evolve, so individuals and businesses seeking insurance coverage in Israel should consult with insurance providers and stay informed about the latest developments in the insurance market. Additionally, insurance policies may vary in terms of coverage, exclusions, and pricing, so it’s essential to carefully read and understand the terms and conditions of any insurance policy before purchasing it.

Investment funds

Israel has a thriving investment fund industry that provides various investment opportunities to both domestic and international investors. These investment funds are managed by professional fund managers and offer a diverse range of assets and investment strategies. Here’s an explanation of Israel’s investment funds and their types:

Mutual Funds: There are two types of mutual funds available in Israel that are mentioned below

Open-End Funds: These are the most common type of mutual funds in Israel. They issue and redeem shares daily at their Net Asset Value (NAV). Open-end funds can invest in a wide range of assets, including stocks, bonds, real estate, and money market instruments.

Closed-End Funds: Unlike open-end funds, closed-end funds issue a fixed number of shares during their initial public offering (IPO). After the IPO, shares are traded on stock exchanges like ordinary stocks. Closed-end funds may trade at a premium or discount to their NAV.

Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs): ETFs are investment funds that trade on stock exchanges, just like individual stocks. They provide exposure to various asset classes and investment strategies. In Israel, ETFs have gained popularity as a cost-effective and liquid way to invest in local and global markets.

Hedge Funds: Hedge funds in Israel are typically offered to accredited investors and institutional investors. They employ various strategies, including long/short equity, event-driven, and global macro, to generate returns. Hedge funds often have higher fees and greater flexibility in their investment approaches compared to traditional mutual funds.

Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs): Israel has a well-developed real estate market, and REITs allow investors to gain exposure to this sector without directly owning physical properties. REITs typically invest in income-generating properties such as commercial real estate, residential complexes, and infrastructure projects.

Private Equity Funds: Private equity funds pool capital from investors to acquire, invest in, or provide financing for private companies. These funds often target startups, growth-stage companies, or distressed businesses. They may have a longer investment horizon and involve higher risks but potentially higher returns.

Venture Capital Funds: Israel is renowned for its vibrant startup ecosystem, and venture capital funds play a pivotal role in funding early-stage and high-growth startups. These funds invest in companies with innovative technologies and significant growth potential.

Money Market Funds: Money market funds invest in short-term, highly liquid, and low-risk securities like government bonds, treasury bills, and commercial paper. They are suitable for investors seeking safety and liquidity while earning a modest return.

Balanced Funds: Balanced funds, also known as asset allocation funds, invest in a mix of asset classes, such as stocks, bonds, and cash equivalents. These funds aim to provide a balanced risk-return profile, making them suitable for investors with moderate risk tolerance.

Sector-Specific Funds: Some funds in Israel focus on specific sectors or industries, such as technology, healthcare, or energy. These funds allow investors to target their investments in areas they believe have growth potential.

Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) Funds: SRI funds incorporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria into their investment decisions. They aim to invest in companies that align with sustainable and ethical principles.

Investors in Israel’s investment funds can choose from a wide array of options based on their risk tolerance, investment goals, and preferences. Before investing, it’s essential to conduct thorough research, consider the fund’s track record, fees, and risk factors, and consult with financial advisors if needed to make informed investment decisions.

Regulatory Authorities

Israel’s financial system is governed by several regulatory authorities that oversee various aspects of the financial industry, ensuring its stability, integrity, and fair operation. These regulatory bodies play a critical role in safeguarding the interests of investors, consumers, and the overall financial health of the country. Here’s an explanation of the key regulatory authorities in Israel’s financial system:

Bank of Israel (BOI): The Bank of Israel serves as the country’s central bank and is responsible for formulating and implementing monetary policy. Its primary objective is to maintain price stability and support the overall stability of the financial system. Its functions include controlling the money supply and interest rates to manage inflation and economic growth, managing foreign exchange reserves to influence the exchange rate, supervising and regulating the banking sector to ensure its safety and soundness, and serving as the lender of last resort to financial institutions in times of crisis.

Israel Securities Authority (ISA): The ISA is the regulatory authority responsible for overseeing the capital market and securities industry in Israel. Its functions include regulating the issuance and trading of securities, including stocks, bonds, and mutual funds, supervising and enforcing rules and regulations related to corporate governance and disclosure by publicly traded companies, protecting investors’ interests and ensuring fair and transparent market practices, and licensing and regulating market participants, such as brokers, investment advisers, and portfolio managers.

Ministry of Finance: The Ministry of Finance is responsible for setting fiscal policy, taxation, and economic policies in Israel. Its functions include formulating and implementing budgetary and fiscal policies to support economic stability and growth, administering taxation, including income tax, corporate tax, and value-added tax (VAT), and managing government expenditures and public finance.

Insurance and Pension Supervision Department: This department operates under the Ministry of Finance and is responsible for regulating and supervising the insurance and pension sectors in Israel. Its functions include overseeing insurance companies, ensuring their financial stability, protecting policyholders, regulating and supervising pension funds to safeguard the retirement savings of individuals, and setting rules and standards for insurance and pension products.

Israel Money Laundering and Terror Financing Prohibition Authority (IMPA): IMPA is responsible for preventing money laundering and the financing of terrorist activities within the financial system. Its functions include developing and enforcing anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorist financing (CTF) regulations and guidelines, monitoring financial institutions for compliance with AML/CTF laws, and collaborating with international bodies to combat money laundering and terrorist financing on a global scale.

These regulatory authorities work together to maintain the stability and integrity of Israel’s financial system. They establish and enforce rules and regulations, supervise financial institutions, protect the rights of investors and consumers, and contribute to the overall economic health of the country. Their efforts are crucial in ensuring that Israel’s financial system operates efficiently and transparently, fostering trust and confidence in the financial markets.

Financial Technology (FinTech): Financial Technology (FinTech) plays a pivotal role in Israel’s financial system by driving innovation, enhancing accessibility, and improving the efficiency of financial services. As a global technology hub known for its cutting-edge startups and entrepreneurial spirit, Israel has harnessed its technological prowess to create a thriving FinTech ecosystem. Israeli FinTech companies are at the forefront of developing solutions in areas like digital payments, peer-to-peer lending, blockchain technology, and financial analytics. These innovations not only cater to domestic consumers and businesses but also attract international attention and investment.

By leveraging FinTech, Israel has transformed the way financial services are delivered, making them more user-friendly, cost-effective, and secure. Moreover, the FinTech sector complements the country’s broader economic landscape, especially its thriving high-tech industry, contributing significantly to Israel’s overall economic growth and competitiveness in the global financial arena.

In summary, Israel’s financial system is characterized by a diverse and well-regulated set of institutions and markets that support the country’s economic growth and stability. The government and regulatory authorities work to ensure the system’s integrity and safeguard the interests of investors and consumers. The financial sector also plays a pivotal role in supporting Israel’s dynamic technology and innovation-driven economy.

Israel Credit System

- Overview of the Israel Credit System

- Credit Score in Israel

- Credit Agencies

- Types of Credit Cards in Israel

- Sources of Credit Cards in Israel

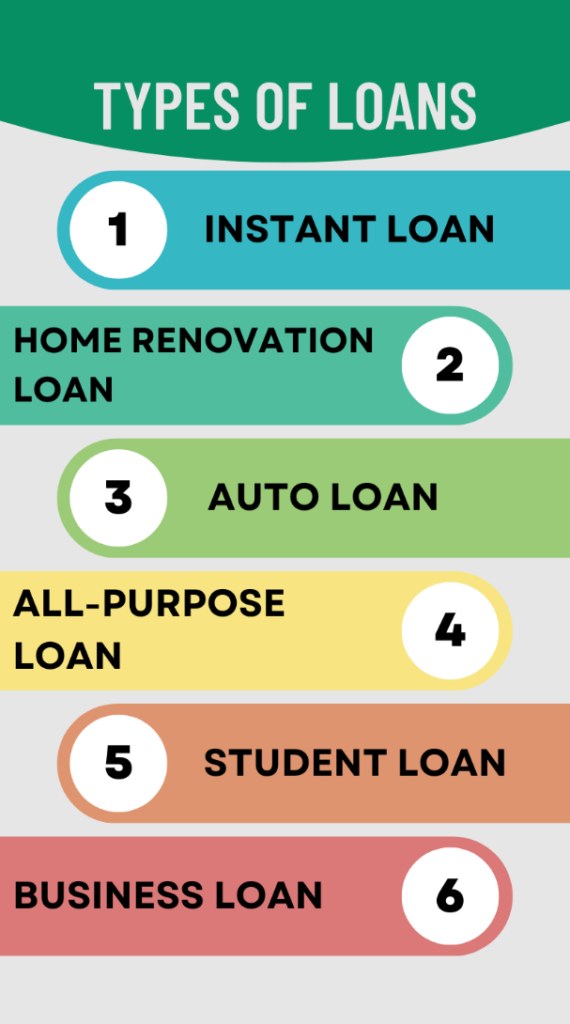

- Types of Loans in Israel

Overview of the Israel Credit System

Israel is making solid progress in building a modern, competitive, and open financial system. Through the mid-1980s, the government took a very active role in the allocation of resources, using direct government credits, capital grants, and guarantees. Between the foundation of the state of Israel in the late 1940s and the mid-1980s, the financial system was characterized by a very high degree of government intervention and control.

This reflected a broader policy of widespread government intervention in the economy for resource allocation and income distribution. Meanwhile, persistently high inflation contributed to financial repression, and through the early 1990s nearly all financial assets were indexed to inflation or foreign currencies, mainly the U.S. dollar.

Banking in Israel is different from banking in other Western countries. Although Israel is a democratic country that allows its citizens to freely conduct business, it is more bureaucratic and this leads to several practical differences. Banks in Israel are more curious about your transactions than in other Western countries where banking secrecy and privacy are respected more.

Banks in Israel charge fees for almost every transaction made. You name it, the banks charge for it! It is something that you need to get used to as a day-to-day reality. Fees for cash withdrawals are usually larger after a certain threshold is reached and if you can plan and withdraw cash in smaller increments you can avoid paying higher fees.

Credit cards are a standard part of financial life however, as an Oleh, you need to be aware that most credit cards issued in Israel are debit cards. The debit will occur once a month and you can select the date that is most convenient for you from a list of several available debit dates.

Credit Score in Israel: Credit scores play a crucial role in financial stability and access to credit, even in countries where they are not widely known. Just like in many other countries, a credit score reflects an individual’s creditworthiness and financial responsibility. The credit score is a numerical representation that is calculated based on various factors such as payment history, outstanding debts, length of credit history, types of credit accounts, and recent credit activities. This score serves as an assessment tool for lenders, banks, and financial institutions when determining whether to extend credit, approve loans, or provide favorable terms.

In Israel, credit scores aren’t widely understood by the public, as they were only put into effect in 2019; however, understanding the importance of credit scores and how they are calculated can help Israelis make informed financial decisions and potentially secure better loan terms.

“The whole system was part of legislation enacted to make the Israeli market more competitive to get more companies to enter the credit market, and we see today that it’s starting to come to fruition.” Anat Gissin.

Israel does not have a centralized credit scoring system like the ones in many Western countries, such as the FICO score in the United States. Instead, Israel has several credit bureaus and financial institutions that maintain their credit databases and scoring methods. These institutions collect information from various sources, including banks, credit card companies, and other financial institutions, to assess an individual’s creditworthiness.

Israel was first rated by credit rating agencies Fitch and Moody’s in 1995. These ratings were made in conjunction with Israel’s first global sovereign bond issuance made without external guarantees.

A strong credit score can lead to better borrowing opportunities and favorable interest rates, while a lower score may limit access to credit or result in less favorable terms. Individuals need to monitor and manage their credit scores responsibly to maintain healthy financial profiles and achieve their financial goals.

Credit Agencies in Israel: Credit agencies in Israel play a vital role in assessing individuals’ and businesses’ creditworthiness. These agencies collect, compile, and analyze financial data to generate credit reports and scores that reflect an entity’s credit history, payment behavior, and financial obligations. The main credit agencies in Israel include the Israeli Credit Insurance Company (ICIC), Experian Israel, and Dun & Bradstreet Israel.

These agencies provide lenders, banks, and financial institutions with valuable information for making informed decisions about extending credit, issuing loans, and setting interest rates. Consumers and businesses can also benefit from these credit reports by gaining insights into their financial health and taking steps to improve their credit profiles.

Credit agencies contribute to the transparency and efficiency of the financial system, enabling responsible lending practices and helping individuals and businesses make well-informed credit-related decisions.

The major credit agencies in Israel are as follows:

The Israeli Credit Insurance Company (ICIC): The Israeli Credit Insurance Company, is the leading credit insurer in Israel. ICIC has been ensuring credit since 1957 and today ensures sales totaling over $15 billion annually, in both local and foreign trade transactions.

ICIC offers varied and advanced credit insurance services as well as programs assisting in obtaining finance and performance guarantees for both domestic and export purposes. The company type is Credit Insurance and Surety. Our lines of bonds and guarantees are written are Bid bonds, Advance Payment bonds, Performance bonds, and Custom bonds.

ICIC is an equal partnership company, jointly owned by Allianz Trade* – the largest credit insurer in the world, and Harel Insurance Investments and Finances Ltd – one of the largest insurance companies in Israel.

Experian Israel: Experian is a well-known global credit reporting and information services company that operates in various countries, including Israel. Experian provides credit-related information, data analytics, and technology solutions to individuals, businesses, and organizations to help them manage risk, make informed decisions, and improve financial health.

Experian Israel is a branch of Experian, a globally recognized credit reporting company. Experian’s services in Israel are likely to be similar to its services in other countries. Experian compiles credit reports that contain information about an individual’s or business’s credit history, payment behavior, outstanding loans, credit limits, and more.

Experian offers identity verification services to help businesses confirm the identity of individuals during various transactions, such as applying for credit, opening accounts, or conducting online transactions. Experian provides tools and services to detect and prevent fraudulent activities. This can include monitoring credit activity for suspicious behavior and assisting in identity theft prevention.

Experian helps businesses assess risk associated with lending, credit extension, and other financial decisions. This information enables lenders to make informed decisions while managing risk effectively.

Dun & Bradstreet Israel: Dun & Bradstreet is a global provider of business information and analytics, offering services related to business credit reporting, risk management, and commercial data insights. Dun & Bradstreet also operates in Israel, providing businesses with valuable information and insights to assess credit risk, make informed business decisions, and manage relationships with other companies.

Dun & Bradstreet Israel is known for providing business credit information and ratings. With Dun & Bradstreet’s Consumer Credit Report, you can learn about the finances of a private person, subject to the Consumer Credit Law. This law does allow a high level of accessibility to information about individuals’ compliance with their financial obligations.

The information in the Consumer Credit Report is gathered from a variety of bank and state sources. Using it, you can minimize any ambiguity about a potential business partner and avoid entering into any ill-advised business transactions.

Types of Credit Cards

Credit cards are the dominant payment method in Israel, followed by debit cards. Debit cards from Visa or Mastercard are popular among teenagers and are usually co-branded with a local scheme. To buy from international businesses, Israelis need to pay with a Visa or Mastercard, but they don’t use these schemes for domestic payments.

You may have heard that Israeli credit card rewards and perks are just not that exciting relative to cards in many other countries, this is true. Most Israeli credit cards have high fees with close to 0 benefits. That being said, there are some cards here with significant advantages over the standard card issued by your Israeli bank and it may be a good time for an upgrade.

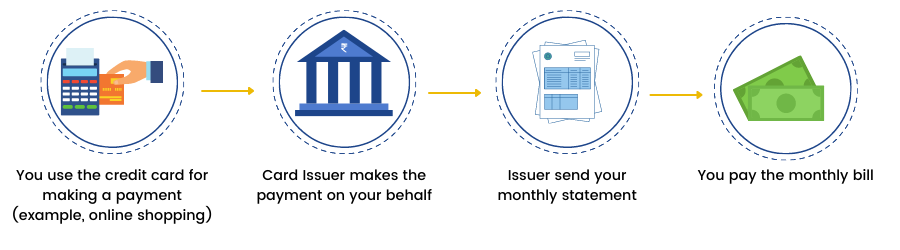

How Credit Card Works: In Israel, the bank offers a range of credit cards to suit your individual needs. Some of the main types of credit cards are:

Visa Credit Card: The most widely accepted credit card brand in the world for its benefits, promotions, and discounts. Visa credit cards are widely used and offered by various financial institutions in Israel, just like in many other parts of the world. Visa is one of the major international payment networks, and its credit cards can come in various types and with different features, depending on the issuing bank or financial institution.